By – James M. Katz, BA

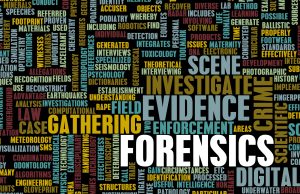

In the intersection between healthcare and the justice system, forensic nurse specialist emerge as a pivotal figure, blending the compassion of nursing with the analytical acumen required for crime scene investigation. Their unique role encompasses not only providing trauma-informed care to victims but also collaborating closely with medical examiners and legal professionals to ensure accurate evidence collection and documentation. Forensic nursing, a discipline that has only gained formal recognition in recent decades, now stands as a vital component of both the medical and legal communities, bridging gaps that were once challenging to overcome. This role’s importance is magnified in cases involving vulnerable populations, where forensic nurse examiners utilize their specialized skills to advocate for those who may not be able to speak for themselves. Forensic nursing specialists play a unique role in the healthcare and legal systems. They bridge the gap between medical care and the law, helping victims of violence and crime. These nurses not only provide medical care but also collect and document evidence, working closely with legal authorities. Their work is crucial in ensuring justice and support for those affected by crime.

In the intersection between healthcare and the justice system, forensic nurse specialist emerge as a pivotal figure, blending the compassion of nursing with the analytical acumen required for crime scene investigation. Their unique role encompasses not only providing trauma-informed care to victims but also collaborating closely with medical examiners and legal professionals to ensure accurate evidence collection and documentation. Forensic nursing, a discipline that has only gained formal recognition in recent decades, now stands as a vital component of both the medical and legal communities, bridging gaps that were once challenging to overcome. This role’s importance is magnified in cases involving vulnerable populations, where forensic nurse examiners utilize their specialized skills to advocate for those who may not be able to speak for themselves. Forensic nursing specialists play a unique role in the healthcare and legal systems. They bridge the gap between medical care and the law, helping victims of violence and crime. These nurses not only provide medical care but also collect and document evidence, working closely with legal authorities. Their work is crucial in ensuring justice and support for those affected by crime.

This article delves into the multifaceted world of forensic nursing, outlining the roles and responsibilities that define a forensic nurse specialist, from the initial crime scene investigation to providing expert testimony in court. It explores the various types of forensic nurses, including forensic nurse death investigators and forensic nurse consultants, and discusses the educational pathways and forensic nursing certifications necessary to enter this field. Furthermore, it highlights the diverse work settings a forensic nurse may find themselves in, the essential skills and competencies required for success, and the unique challenges and rewards that come with the job. Finally, it reflects on the future prospects in forensic nursing, providing insight into how this profession continues to evolve and expand its impact on healthcare and the legal system.

Key Takeaways

- Forensic nursing specialist helps both victims and perpetrators by providing medical care and collecting evidence.

- To become a forensic nursing specialist, one must first be a registered nurse and then pursue advanced education and certification in forensic nursing.

- There are different types of forensic nursing specialties, including Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners, Psychiatric Forensic Nurses, and Legal Nurse Consultants.

- Forensic nursing specialists need a mix of medical knowledge, legal understanding, and strong communication skills.

- These specialists can work in various settings such as hospitals, law enforcement agencies, and community services.

Overview of Forensic Nursing

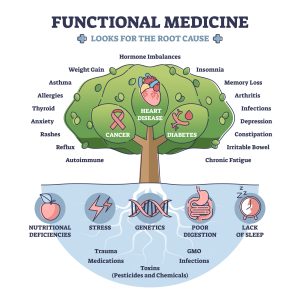

Definition and Scope

Forensic nursing, as defined in the “Forensic Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice,” is the application of nursing practice globally where health and legal systems intersect. This specialty involves integrating nursing knowledge with forensic science to provide specialized care to patients involved in legal cases. Forensic nurses are trained health professionals who treat the trauma associated with violence and abuse, such as sexual assault, intimate partner violence, neglect, and other forms of intentional injury. They also play a critical role in anti-violence efforts, collecting evidence and offering testimony that can be used in court to apprehend or prosecute perpetrators.

Historical Background

The roots of forensic nursing can be traced back to early civilization, with documented evidence suggesting that ancient Egyptian and Hindu medicine recognized the concepts of poisons and toxicology. This understanding was further developed by Greek and Roman civilizations, which discussed injury patterns and used them to determine causes of death. The integration of forensics into nursing, however, began much later. In the United Kingdom during the 1950s, forensic nursing practices were documented, where nurses partnered with law enforcement to provide both healthcare and forensic medicine within custodial environments.

In the United States, the formal inception of forensic nursing occurred in the 1970s with the establishment of the first Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) programs. These programs were developed as nurses recognized the inadequate services provided to victims of sexual assault compared to other emergency department patients. The first SANE programs started in Memphis, Tennessee in 1976, followed by Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1977, and Amarillo, Texas in 1979 . The role of SANEs expanded significantly in 1992 with the formation of the International Association of Forensic Nurses and was recognized as a nursing subspecialty by the American Nurses Association in 1995. This historical progression highlights the evolution of forensic nursing from an informal practice to a specialized field that bridges the gap between healthcare and the legal system, ensuring that victims of violence and abuse receive both compassionate care and justice.

Roles and Responsibilities of a Forensic Nurse Specialist

Patient Care

Forensic nurse specialist provides comprehensive care to individuals who have experienced trauma or violence. They blend holistic nursing care focusing on the body, mind, and spirit with expertise in legal and forensic disciplines. This dual focus ensures that both the medical and evidentiary needs of patients are met. Forensic nurses treat a wide range of traumas, including those from sexual assault, domestic violence, and other violent crimes. Their approach is invariably trauma-informed, ensuring that patients feel safe and supported throughout their care.

Evidence Collection

A critical aspect of the forensic nurse’s role is the collection and preservation of evidence. This process is meticulous and governed by strict protocols to ensure that the evidence can be used in legal proceedings. Forensic nurses are trained in the proper techniques for documenting injuries, collecting biological samples, and maintaining the chain of custody for all collected evidence. Their detailed attention to the process ensures that the evidence gathered can withstand rigorous scrutiny in court.

A critical aspect of the forensic nurse’s role is the collection and preservation of evidence. This process is meticulous and governed by strict protocols to ensure that the evidence can be used in legal proceedings. Forensic nurses are trained in the proper techniques for documenting injuries, collecting biological samples, and maintaining the chain of custody for all collected evidence. Their detailed attention to the process ensures that the evidence gathered can withstand rigorous scrutiny in court.

Legal Testimonies

Forensic nurses often serve as both fact and expert witnesses in court. As fact witnesses, they testify only about what they observed and the actions they performed during the course of their duties. This might include details of the forensic examination and the protocols followed. As expert witnesses, they are permitted to provide opinion testimony based on their specialized knowledge and experience. This can cover areas such as the interpretation of medical findings, victim behavior during examinations, and the implications of specific injuries. Their testimony is highly valued due to their perceived neutrality and professional expertise. Forensic nurses must maintain a high level of professionalism and objectivity when involved in legal proceedings. They are expected to present their findings honestly and without bias, contributing effectively to the administration of justice.

Types of Forensic Nurses

Forensic nursing encompasses various specialized roles, each critical to bridging the gap between healthcare and legal systems. This section highlights three primary categories of forensic nurses: Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), Nurse Coroners, and Forensic Psychiatric Nurses.

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs)

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners provide crucial care and forensic examinations to victims of sexual assault. Their responsibilities extend beyond medical treatment to include forensic evidence collection, which is vital for legal proceedings. SANEs conduct detailed interviews and physical examinations, ensuring the collection of forensic evidence while maintaining the dignity and privacy of the victim. They also play a significant role in providing testimony in court, where their expert insights contribute to the judicial process.

Nurse Coroners

Nurse Coroners, also known as nurse death investigators, work closely with medical examiners and coroners to determine the causes of death. Their role is integral in settings such as coroner offices, forensic units, and law enforcement agencies. These professionals are skilled in conducting external examinations, collecting biological samples, and documenting findings crucial for legal and investigative purposes. Their work often uncovers critical information that can impact public health policies and criminal justice proceedings.

Forensic Psychiatric Nurses

Forensic Psychiatric Nurses specialize in the care of individuals who are involved with the legal system, particularly those who may have mental health issues. They evaluate and treat both victims and offenders, providing essential mental health services and support. These nurses work in diverse environments, including correctional facilities, psychiatric institutions, and behavioral health centers. The role requires a high level of expertise in mental health and an ability to remain unbiased and supportive in challenging situations.

Each of these roles demonstrates the diverse capabilities and critical importance of forensic nurses in integrating medical care with judicial and investigative processes. Their specialized skills ensure that individuals receive comprehensive care and support while contributing to the broader goals of justice and public safety.

Roles and Responsibilities of a Forensic Nursing Specialist

Providing Care to Victims and Perpetrators

Forensic nursing specialists play a crucial role in caring for both victims and perpetrators of crimes. They offer medical attention, emotional support, and ensure that patients receive the necessary follow-up care. Their work is essential in bridging the gap between healthcare and the legal system.

Evidence Collection and Documentation

One of the key responsibilities of a forensic nursing specialist is to collect and document evidence. This includes taking photographs, collecting samples, and meticulously recording observations. Accurate documentation is vital for legal proceedings and can make a significant difference in the outcome of a case.

Collaboration with Legal Authorities

Forensic nursing specialists often work closely with law enforcement and legal professionals. They may be called upon to testify in court, provide expert opinions, and assist in investigations. Their collaboration ensures that the medical and legal aspects of a case are thoroughly addressed, contributing to the pursuit of justice.

Educational Pathways to Becoming a Forensic Nursing Specialist

Registered Nurse Prerequisites

To start your journey as a forensic nursing specialist, you first need to become a registered nurse (RN). This involves completing an Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) or a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program. After finishing your degree, you must pass the NCLEX-RN exam to get your RN license. Gaining experience as an RN is crucial before moving on to specialized forensic nursing roles.

Advanced Degree Programs

Once you have some experience as an RN, you can pursue advanced degrees that focus on forensic nursing. Master’s programs often offer specializations in areas like sexual assault examination, psychiatric forensic treatment, and protective service investigation. These programs prepare you for more advanced roles and responsibilities in the field.

Continuing Education and Certification

Continuing education is essential for staying updated in forensic nursing. You can take specialized courses and earn certifications such as the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) or the Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing Certification (PMH-BC). These certifications not only enhance your skills but also make you more competitive in the job market.

Work Settings

Forensic nurses find a wide array of employment opportunities across different settings, each offering unique challenges and requiring specialized skills. These professionals are integral not only in healthcare facilities but also within the criminal justice system, where they apply their expertise in both medical and legal arenas.

Hospitals

In hospital settings, forensic nurses often engage in emergency departments and sexual assault centers, where they address the immediate needs of victims of violence and sexual assault. They are tasked with performing forensic examinations and providing trauma-informed care, often working in tandem with other healthcare professionals to ensure comprehensive patient care.

Community Programs

Forensic nurses also play a crucial role in community anti-violence programs. They work alongside law enforcement, social workers, and public health organizations to develop and implement strategies that prevent violence and support victims. Their responsibilities may extend to participating in community crisis responses, such as in the aftermath of mass disasters or in situations involving widespread community trauma.

Legal Institutions

Within the legal system, forensic nurses may work in various capacities, such as in coroners’ and medical examiners’ offices where they assist in determining causes of death and collecting crucial evidence for criminal investigations. Additionally, they often serve as liaisons between healthcare services and the justice system, helping to ensure that victims’ rights are upheld and that evidence is properly handled and presented in court. In each of these settings, forensic nurses must adapt to the demands of their work environment while maintaining a high standard of care and adhering to legal and ethical guidelines. Their ability to navigate between the worlds of healthcare and law makes them invaluable in bridging the gap between these two critical fields.

Skills and Competencies Required

Forensic nurse specialists must possess a blend of clinical knowledge and soft skills to excel in their multifaceted roles. Here are the essential skills and competencies required for this challenging yet rewarding field:

Interpersonal Skills

Empathy, sensitivity, and the ability to establish trust are paramount in dealing with patients and their families. These skills are crucial for forensic nurses who often work with individuals affected by traumatic events. The nurturing of a trusting relationship can significantly impact the effectiveness of patient care and the overall investigative and legal process.

Communication Skills

Clear and concise documentation of medical findings is essential, as is the ability to collaborate effectively with multidisciplinary teams, including law enforcement and legal professionals. Forensic nurses must articulate complex medical information in a manner that is understandable in both medical and legal contexts, ensuring accuracy and adherence to procedural protocols.

Attention to Detail

Forensic nurses are required to perform precise documentation of evidence and thorough patient assessments. These tasks are critical not only in providing high-quality patient care but also in ensuring that the evidence collected can withstand legal scrutiny during court proceedings.

Problem-Solving Skills

The ability to think critically and make quick decisions under pressure is vital, especially in time-sensitive situations that forensic nurses often encounter. This skill set enables them to manage the complexities of cases involving trauma and to navigate the challenges that arise during forensic examinations.

Cultural Competence

Understanding and appreciating cultural differences is essential in providing appropriate and sensitive care to diverse patient populations. Forensic nurses must be equipped to address and respect these differences, which can significantly affect the therapeutic and legal aspects of their role.

Trauma-Informed Care

Forensic nurses must be adept at providing trauma-informed care, which involves understanding the various sources of trauma and implementing care strategies that support healing and reduce re-traumatization. This approach is crucial in handling cases sensitively and effectively, acknowledging the profound impact trauma can have on individuals.

Legal Knowledge

A thorough understanding of legal principles and procedures is crucial for forensic nurses. They must be well-versed in the legal standards and ethical considerations of nursing and healthcare to effectively participate in the judicial process, from evidence collection to providing testimony in court.

Each of these skills and competencies plays a critical role in enabling forensic nurses to fulfill their duties effectively, bridging the gap between healthcare and the legal system, and ensuring that patients receive both compassionate care and justice.

Challenges and Rewards

Emotional Toll

The emotional toll on forensic nurses is significant, as they frequently encounter patients who have experienced severe trauma and violence. The constant exposure to such distressing situations can lead to vicarious trauma, where nurses experience emotional disturbances from empathizing deeply with their patients’ suffering. This repeated exposure often results in burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion and a feeling of being overwhelmed by their responsibilities. Studies indicate that a substantial percentage of nurses, including forensic nurses, have reported high levels of burnout, with findings showing that 62% of nurses experienced burnout in 2020. The emotional toll is further compounded by the frustration and anxiety that can arise from involvement in legal cases, which may lead to job dissatisfaction and mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety.

Professional Satisfaction

Despite the challenges, working as a forensic nurse also brings profound professional satisfaction. Forensic nurses play a crucial role in the healthcare system by providing essential trauma-informed care to victims of violence and abuse. The ability to make a significant difference in the lives of patients during their most vulnerable moments is highly rewarding. Many forensic nurses find fulfillment in seeing the tangible results of their care, as patients recover from their initial state of trauma to a more stable and engaged condition during treatment. Moreover, the job offers unique benefits such as the opportunity to fight for justice for victims, potentially higher salaries compared to other nursing roles, and the satisfaction of knowing they have helped bring perpetrators to justice. This sense of accomplishment and the ability to advocate for and support victims provide a strong counterbalance to the emotional challenges faced in this field.

Future Prospects in Forensic Nursing

The field of forensic nursing is experiencing significant growth, driven by increasing public health demands and the evolving complexities of legal and healthcare systems. In 2021, the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) saw a 27 percent increase in applications for certification, reaching a record high of 1,213 applicants . This surge underscores the expanding role and recognition of forensic nurses in addressing crime, abuse, and violence.

Career Growth

Forensic nursing offers diverse career paths that extend beyond traditional nursing roles, allowing for specialization and advancement. The most common specialization is the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE), who plays a crucial role in treating and examining victims of sexual assaults. For those looking to expand their expertise, roles such as forensic psychiatric nurse, legal nurse consultant, and nurse coroner provide avenues for professional growth. Continuous education and obtaining specialized certifications are essential for advancing in these roles, enhancing both the scope of practice and the impact on community safety and patient care.

Hospitals and Medical Centers

Forensic nurses often work in hospitals and medical centers, providing care to patients who have experienced trauma or violence. They play a crucial role in collecting evidence and documenting injuries to support legal cases. Their expertise is vital in ensuring that victims receive the care they need while also preserving important forensic evidence.

Law Enforcement Agencies

Forensic nurses collaborate with law enforcement agencies to assist in criminal investigations. They may be called upon to examine victims and suspects, collect evidence, and provide expert testimony in court. Their medical knowledge and forensic skills are essential in helping to solve crimes and bring justice to victims.

Community and Social Services

In community and social service settings, forensic nurses work with vulnerable populations, including victims of abuse and neglect. They provide medical care, support, and advocacy to help individuals navigate the legal system and access necessary resources. Their work is critical in promoting the health and well-being of those affected by violence and trauma.

Challenges and Rewards in Forensic Nursing

Emotional and Psychological Impact

Forensic nursing can be emotionally tough. Nurses often deal with victims of serious crimes, which can be hard to handle. Seeing the pain and suffering of others can take a toll on their own mental health. They need to be strong and find ways to cope with the stress.

Professional Fulfillment

Despite the challenges, being a forensic nurse specialist can be very rewarding. Helping victims and making sure they get justice can bring a lot of satisfaction. Knowing that their work makes a real difference in people’s lives can be very fulfilling. The sense of purpose and achievement is a big part of why many choose this career.

Ethical Dilemmas

Forensic nurses often face tough ethical choices. They have to balance their duty to care for patients with the need to collect evidence for legal cases. This can sometimes lead to difficult decisions. Navigating these ethical dilemmas requires a strong sense of right and wrong.

Emerging Trends

Forensic nursing is increasingly recognized as a critical component of the forensic sciences, integrating with disciplines within the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) to enhance investigative and clinical practices. The field is advancing with the help of scientific techniques, including the use of Artificial Intelligence and digital documentation, which are pivotal in the collection and preservation of fragile biological evidence. Legislative support, such as the collaboration between SANE nurses and military physicians mandated by the U.S. Congress in 2014, highlights the growing acknowledgment of the role forensic nurses play in societal safety and justice.

Furthermore, the establishment of the Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC) for Forensic Sciences by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2014 aims to standardize forensic practices. The OSAC’s Forensic Nursing Subcommittee is drafting standards specifically for sexual assault evaluations, aiming to improve care quality and legal outcomes.

The global outlook for forensic nursing is also expanding. The AAFS Forensic Nursing Science (FNS) Section is working internationally to promote forensic nursing education and practice, aiming to establish a universal forensic health paradigm by 2024. This includes efforts to enhance global humanitarian initiatives and support vulnerable populations in regions affected by crime and human rights violations. As forensic nursing continues to evolve, it remains at the forefront of bridging healthcare and legal systems, providing critical services that extend far beyond traditional nursing roles. The future of forensic nursing not only promises expanded opportunities for nurses but also greater contributions to public safety and justice.

Conclusion

As we have explored, the unique intersection of healthcare and the justice system navigated by forensic nurse specialists underscores the significant and evolving role these professionals play in both fields. Their work, which spans from providing compassionate care to victims of violence and trauma to the meticulous collection and documentation of evidence for legal proceedings, illustrates the multifaceted nature of this discipline. Through their dedication and specialized expertise, forensic nurses not only support individuals during their most vulnerable times but also contribute to the broader objectives of justice and public health.

Looking ahead, the field of forensic nursing stands on the cusp of further expansion and recognition. The growing demand for forensic nurse specialists, fueled by the complexities of modern legal and healthcare systems, presents opportunities for career growth and development. As forensic nursing continues to develop its scope and impact, its practitioners will play an increasingly vital role in braiding the gap between patient care and legal advocacy, highlighting the profession’s critical contribution to society’s well-being and safety.

If you’re a registered nurse and want to become a certified Forensic Nursing Specialist then you should review our Forensic Nurse Specialist program. We offer 5 online Forensic Nursing courses that are required to qualify for certification. Once complete you would be a Certified Forensic Nurse Specialist with us for a period of 4 years. To review our courses as well as our requirements, please go here to our Forensic Nurse Specialist Certification program

FAQs

- What responsibilities does a forensic nurse have within a hospital setting?

A forensic nurse is pivotal in providing holistic care to victims of violence. Their responsibilities include performing detailed medical forensic examinations, collecting evidence, providing testimony in court, and offering compassionate support to survivors. - Why is legal knowledge significant for forensic nurses?

Forensic nurses need to be meticulous and aware of the legal aspects of their role since they handle evidence that could be used in court. They are responsible for ensuring that the evidence collection process is thorough and legally sound, maintaining the integrity of the chain of custody. - What is the main objective of forensic nursing?

The primary aim of forensic nursing is to blend healthcare with criminal justice to enhance patient care. Forensic nurses focus on understanding the context of injuries, delivering evidence-based care, and facilitating the criminal justice process to ensure comprehensive patient support. - Can you give an example of where forensic nurses are employed?

Forensic nurses are found in various sectors, including roles like Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), and positions dealing with domestic violence, child abuse, elder abuse, death investigations, correctional facilities, and disaster response scenarios. - What does a forensic nursing specialist do?

A forensic nursing specialist helps victims and suspects of crimes. They collect and document evidence and work with law enforcement. - What education is needed to become a forensic nursing specialist?

You need to be a registered nurse first. Then, you can pursue advanced degrees and certifications in forensic nursing. - What types of forensic nursing specialties exist?

There are several, including Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner, Psychiatric Forensic Nurse, and Legal Nurse Consultant. - Where can forensic nursing specialists work?

They can work in hospitals, law enforcement agencies, and community services. - What skills are important for forensic nursing specialists?

They need medical knowledge, an understanding of legal and ethical issues, and good communication skills. - What are the challenges and rewards of being a forensic nursing specialist?

The job can be emotionally tough but also very rewarding. It involves ethical dilemmas but offers professional fulfillment.

Research Articles:

Forensic Nurse Hospitalist: The Comprehensive Role of the Forensic Nurse in a Hospital Setting. Kelly Berishaj DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, SANE-A, Et Al,Journal of Emergency Nursing Volume 46, Issue 3 , May 2020, Pages 286-293

Access link here

Forensic Nursing and Healthcare Investigations: A Systematic Review. Rajiv Ratan Singh, Et Al. International Medicine, Published: Nov 3, 2023

Access link here

Forensic Nurses’ Understanding of Emergency Contraception Mechanisms: Implications for Access to Emergency Contraception. Downing, Nancy R. PhD, RN, SANE-A, SANE-P, FAAN1; Et Al. Journal of Forensic Nursing 19(3):p 150-159, 7/9 2023.

Access link here

Forensic Nursing. Dzierzawski, Brenda MSN, RN, SANE-A. AJN, American Journal of Nursing 124(1):p 47, January 2024.

Access link here

Meta Description