All human beings are called to know, love and serve God. This is a Divine mandate that answers to the virtue of justice. Within justice, the amount of what is due is given to the other. In the case of God, His creation owes to Him worship and service, but God in His infinite love and mercy, has not only made us His creation but also His children. By making us in His own image and likeness, He has called us into a real spiritual dialogue and relationship with Him. Through grace, He has elevated us to the underserved titles of “sons and daughters”.

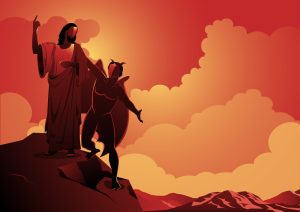

Through free will, God gives us the choice to exist in this state of happiness or to choose our own happiness. Like the demons before, many individuals reject this offer and use their gift of free will to their damnation. Instead of knowing, loving and serving God, they choose to know the world, love oneself and serve indirectly Satan. They walk away from the banner of Christ and instead choose the quick and easy road of immediate pleasure and vice that destroys the soul.

Each person beyond the basis of justice to know, love and serve the Lord, has unique a vocation or particular calling that is beyond our universal call to know, love and serve God. There are different types of callings and vocations within life that compliment one’s universal calling. One fulfills vocation when one offers to Christ all actions, no matter how mundane, and through God’s grace turns the ordinary events of the day into extraordinary events by tying them to Christ as one’s High Priest. Every decision in one way or another is a decision that leads one to our ultimate end which is God. In this blog, we will discuss vocations that are general as well as the existential vocation of one’s life and how to better think about, prepare and undertake it.

Spiritual Advisors and Directors are excellent resources to help souls discover their unique path. All souls have a general path that we share through the Church, but we each have special unique trails we can discover through discernment and prayer.. Spiritual Advisors can help souls find these paths and trails and shine light on God’s direction. Please also review AIHCP’s Christian Counseling Certification as well as AIHCP’s Spiritual Direction Program.

VOCATION

We all have a vocation. Christ told the apostles, to pick up their cross and to follow Him. As Christians, we are to know, love and serve God. We are to manifest within our lives the light of Christ to the world. This is our universal vocation. All things we do must either contribute to this, or at least remain neutral and non-detrimental to that function. While spiritually, our vocation to spiritual life is central, we must also fulfill our relational vocations to others. Those in ministry have unique relations as well as those who are married or single. All callings are important and equal when they meet the call of Christ. Our spiritual calling is the highest call of our vocation and this is met through prayer and love of God and neighbor.

As temporal beings, we have many other needs and hence vocational obligations. As stated these temporal things are important to our existence. They must either contribute to our spiritual end, or at least remain neutral and non-hindering to that end. In this way, one’s profession can be seen as a vocation. A father or mother who works long hours to support the children is fulfilling a parental vocation but also a professional one to afford basic care, food, shelter and clothing, as well as service to the employer. Hence any duties in themselves can become daily vocations. Any relationships that need to be cared or tended can also become a daily vocation. Like St Joseph, we offer these daily duties as a worker, father, or spouse to God. Like St. Theresa the Little Flower, we turn the most mundane act of sweeping the convent floors as duties we perform for the glory of God. We hence fulfill our daily duty and vocation and transform something so mundane and ordinary into something extraordinary when we do them with excellence and love of God. These daily events then themselves become prayers to God.

Some events in the day can be distractions to salvation. Events that steal from our primary vocation and end which is God, as well as take energy, time and emotion from our core duties are distractions and illusions of the world. These distractions hope to push us away from our duties to God, self and family. In discernment, when we engage in activities we must diagnose them in accordance with our primary end, our daily duties and responsibilities. Do these actions deviate from our end? Are they inherently sinful in themselves? Are they only an occasion to sin? Are they taking time away from family and God?

St Ignatius in his Spiritual Exercises makes it very simple when making an election or choice in life about doing or not doing something. He suggest imaging standing before the throne of God on judgement day and calculating if the event or decision is helpful towards one’s salvation or detrimental. He also asks us to examine our conscience in any decision as well the action. What are the fruits of the action? What can occur that is good versus bad? Does it correlate with the laws of God? Does the means equate our true end with God, or does the event itself become its own end?

Whenever making a choice or life decision, one must contemplate, seek counsel, and pray. Many callings need thoroughly contemplated. Of course the first and foremost sign is does it meet our final end? Many things can meet this criteria but one must continue to contemplate further to see if this particular and exact choice or decision is meant for someone. For those, usually three callings emerge. The first, ministry, the second marriage, and the final single life. All three vocational callings demand the universal vocation of all humanity but each one has its own unique place in the Mystical Body of Christ. It is important to ensure that these callings and states are not one’s true end, but are means to fulling that end.

For example, marriage, or the religious life are equally beautiful callings but they themselves must not represent the end and culminating aspect of one’s life. Instead they should represent means that help one reach their own end in unison with God’s will. So, if the decision or calling in itself is good and aligns with humanity’s final end, one must begin to discern if it is indeed the calling and way God hopes to utilize us.

This involves not only prayer and counsel, but also evaluation of one’s own will. Recall, the rich man in the Gospel had done everything he was supposed to do but one thing. When Christ asked him to give up all he had and to follow Him, this troubled the man deeply. So many are called but few are chosen because of our own free will. Many times, even not at the cost of sin, our wills do not align with God in a preferred state in life. God does not wish to force us any particular calling, but He does know what we are best suited for and what would give the greatest fulness to us.. We have been equipped with particular spiritual talents to meet the call of God, so when we submit our will to God, we then are ready to move more peacefully and perfectly in this life.

Take into account Mary. She never questioned God. She said to let it be done according to the will of God. St Joseph as well without hesitation took Mary as his wife and raised the Christ child. In all cases, individuals united their will to the will of God. If one is to truly find their vocation, then one must submit oneself to the will of God in humility and obedience. For those that are willing to submit to God, this is good news, but it still represents a difficult decision in discerning. Unfortunately God is not always loud and clear.

Hearing God

We have spoken about living a life first that fulfills one’s general vocation of knowing, loving and serving God. We have also spoke about the importance of fulfilling our daily duty in humility and obedience to God. That same humility and obedience should carry to the fulfillment of His will and service to Him within our particular calling.. Yet hearing and discerning can sometimes be difficult.

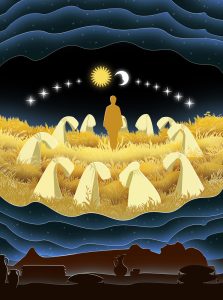

The noises of the world can sometimes drown out God’s voice. We need to direct ourselves in prayer and meditation and seek counsel as needed but there are a few inherent signs of a particular calling (and when I say calling, I mean any calling, marriage, singlehood, monastic life, or priesthood). Being first and primary a disciple of Christ, there are certain signs the Holy Spirit showers us with. Sometimes, we may feel these signs and interior voices through the sacraments or the reading of Scripture, or while doing penance, or working with the poor. Other times, indirect statements from strangers, or signs throughout the day can redirect one to the manifestation God is trying to display.

In addition to signs and coincidences, our own inner self plays a key role. We naturally gravitate towards what God has deemed for us. If we feel a strong connection to a family with children, then our vocation could very well be the married life, or if we see and feel the grace of a minister or priest who proclaims the Gospel, this may be a inward desire towards that. In addition, our skill, talents and spiritual charisms are many times tied to the vocation or calling that God desires for us. Someone well trained in theology may very well be prepared to preach the Gospel at some level, lay or clerical, or may be called for higher levels of Church administration. Those blessed with leadership skills, communicative skills, and higher academic achievement in studies may have a calling within Christ’s Church to lead. Others may be more introvert but spiritual and feel a calling to a more private life with God in a monastery. Others may have a calling to love another person and to share in the creation of new lives. In this calling, they possess the qualities for partnership and compassion, while someone with a ministry or single life calling may naturally be more inclined to a life that is solitary.

God sometimes also pushes one to one’s particular vocation through the presence of need. When someone sees the lack of religious or short handed churches, or less care for the poor, or less advocates for the weak and sick, then these are ways God instills into the soul a yearning to act. These calls to action can feel very personal and one may have a strong passion residing inside to meet that need.

So while God can awaken us the way he did with Saul via an intense vision and conversion, He usually respects our free will and subtly turns so we need to be attentive and listening. It involves our humility and obedience to Him and most importantly our love for God. We need to put God first and live a life that is based on decisions that reflect God and His laws. When our conscience is well formed and sound, it can guide us to a position to truly discern and hear God.

St Ignatius again points out that messages from God, direct or indirect, reflect our holy end. Discernment that leads to selfish ends, or immoral pursuits, or the production of bad fruits, are not from God. So it is important to discern the nature of the election or decision, the objective reality of the choice and its consequences and to place it in subjugation to the laws of God. Then and only then can we see beyond our universal end and see what is also our particular end.

Finding Peace in the Anxiety

Giving our day to God is the first step in finding peace and removing anxiety. When the soul attaches it’s will to the Father, then it fears less. It sees the bumps and discomforts of life, but sees them as happy crosses to suffer for. The soul indeed soon discovers that God always has a plan. So while one worries about one’s career, or if they should marry, or enter the religious life, or if they feel ambivalent in their social life’s decisions with their religious beliefs and unsure where to go, if we simply give God each day, then we can find some peace and direction.

Anxiety comes from the evil one. It comes from association with things of the enemy. St Ignatius points out two standards. The standard of Christ and His banner, or the standard of Satan which is of this world. When consciously or even indirectly choose things that are bad and of Satan’s banner, the fruit will produce. The temptations and lies of this world associated with certain callings can never give true clarity, happiness and peace. Only placement in Christ can our true ultimate end be met. We may experience natural tremors in this life. We may suffer our daily crosses, but these types of anxieties are far different when aligned with Christ.

To remain within the standard of Christ and discover our particular calling one must turn to prayer. Prayers to the Holy Spirit for wisdom, understanding and knowledge, and for the virtue of fortitude and temperance in daily dealings can help a person face each day with the necessary grace and guidance from God. God desires peace and calmness in our life. He understands that we exist in a fallen world and bad things can occur, but He is willing to walk with us and guide us. He also helps us to avoid the temporal noises that are detrimental to our calling. The devil utilizes the noises of anxiety and insecurity mixed with multiple detours that take from the time God deserves–hence these virtues serve as important protections. In our daily life, we must make the ordinary become extraordinary by giving to God each task. As each day becomes a prayer, then one becomes more open to the grand plan of one’s life. Each day given to God leads to the next which builds upon each other until in reveals the beauty of God’s plan. This should remove anxiety because God loves us. He loves us and wishes for us to be happy. He also grants us numerous choices in our independence. God wants our love and respects our choices in this life. However, there will always be a inner movement towards what the soul was designed for and how blessed are individuals who answer the call that God ordained for them.

The quickest way to eventual find one’s unique calling and avoid the noises of Satan and the world is unifying one’s will to God. When our will becomes one with God, then our decisions align regarding daily duties, as well as long term callings. Each day, one should unite their will to God. This is not subjugation or control but a passive release to become aligned with God. God’s will is not one of pain and suffering, those things spar from the world, sin, our choices and Satan. God’s will is for our peace and wholeness with Him. When we unite our wills His, we show humility and obedience, as Mary and Joseph showed to God’s plan. When these wills meet, not only will we discover our long term calling, but God will also guide us through our daily duties with better clarity and peace. Even when loss, suffering and hardships occur, the soul that unites wills with God, will find consolation and direction. God’s will is ultimately joy not control. It is the map to one’s salvation as well as to one’s individual calling. It seeks to direct us so we can have peace and love. It should not be seen as a sentence to serve but a partnership that is for our own best interest. When we choose the standard of Satan, we choose us, we choose the world, we choose things that are detrimental to spiritual growth and peace. The moment the soul surrenders and trusts God over self, then daily duties and overall callings will manifest with graces equipped to help one face all crosses and obstacles and most importantly, to find peace in life.

In the meantime, if one is discerning marriage, or priesthood, continue to pray for guidance but do not allow thoughts of the future that are far away to cloud the present day. The present day is rich with opportunities to please God and fulfill our daily vocation. When individuals focus and allow anxiety to haunt them in regards to their future, they sometimes miss the moments before them. The vocation of the present is just as important as the vocation of the future. Today itself is a prayer and opportunity to know love and serve God. It will build habits that may enable us one day to fulfill that calling more perfectly. As Padre Pio rightfully saw, spiritual development is a motion of growing closer to God overtime. The stagnant soul is unable to grow, or feel, or love, but the soul that is in process, even if far away from the finish line, is moving towards his or her ultimate end. This is important to remember in monitoring spiritual anxiety as well as contemplating one’s vocation.

Conclusion

A vocation and a special calling beyond our daily life is exciting. We should not fear it or become obsessed and anxious over it. God loves us in the moment and we must remember that. We need to tie our will to God so we can better fulfill that vocation. God’s choices for us are for all well being in all facets, while the standard of Satan and self leads to illusions of happiness which cause anxiety, anger and depression. We do not wish to be as Jonah fleeing God’s will. We know as he fled Nineveh, he was swallowed by a large fish, only to be released 3 days later. So we cannot flee our vocation, but we must realize beyond our duty to know, love and serve God, that we are also called in a special way with special talents to grow the Church and Christ’s Mystical Body on Earth. We need to be receptive of this, know how to discern it, and how to listen and respond to it. This involves unifying one’s own will and desires with God and trusting the path that God has plotted for us.

In the meantime, pray everyday for grace to fulfill daily duties with excellence but also illumination to truly understand one’s calling. Please also review AIHCP’s Christian Counseling Certification as well as its Spiritual Direction Program

Additional Blogs

Early Issues in Spiritual Direction. Access here

Spiritual Discernment: Access here

Spiritual Desolation: Access here

Crisis and Doubt in Faith. Access here

Additional Resources

Vocations. Ignatian Spirituality. Access here

Chapman, A. “5 Examples of Vocation in the Bible (And Lessons to Learn from the Stories)”. Access here

Mosseau, J. “How to Discern Your Vocation [+ Tips for Discerning Religious Life]”. University of San Diego. Access here